|

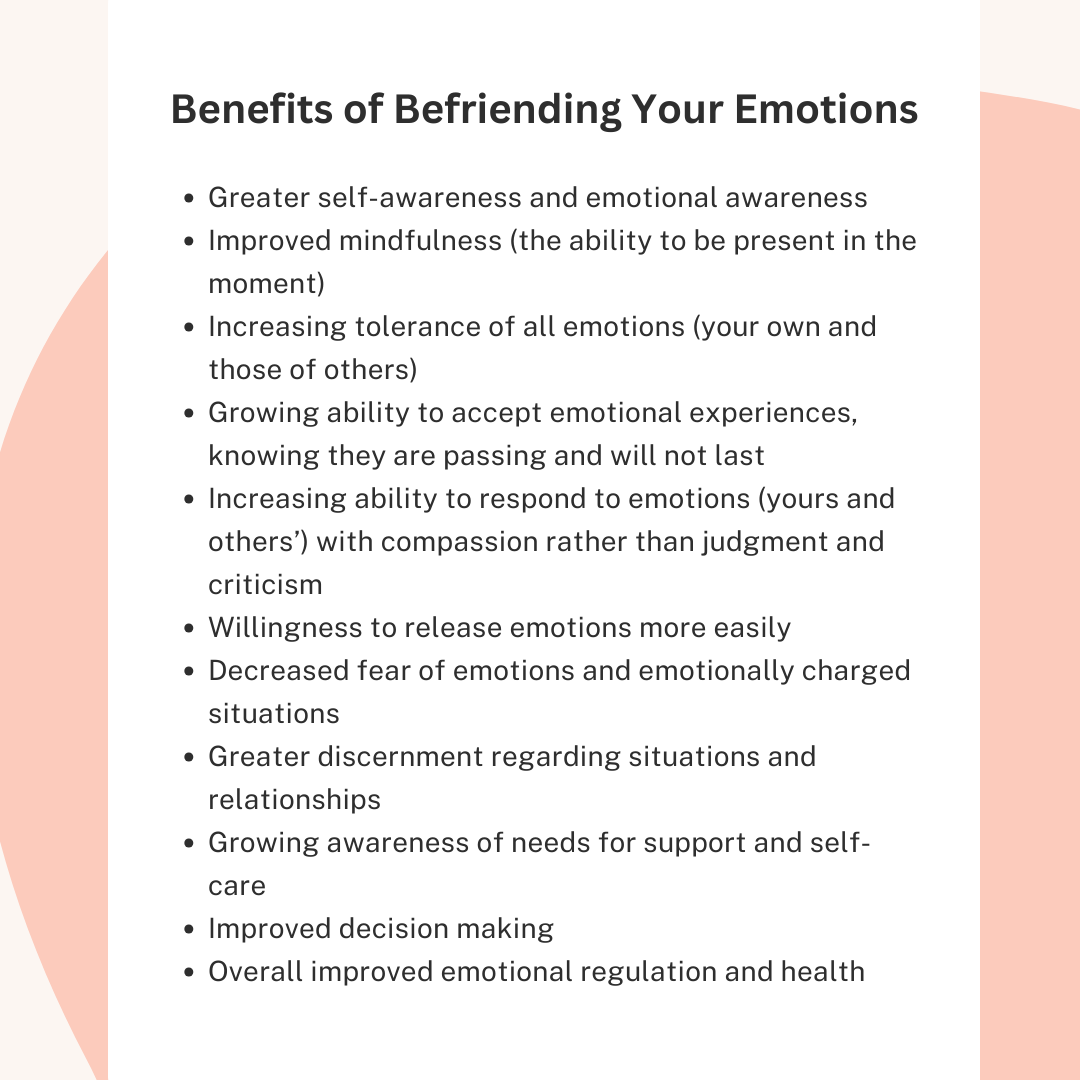

There’s a popular saying that packs a wealth of wisdom: You have to feel it to heal it. Our emotions are gifts of God intended to give us important information about what’s happening within us so we can gain understanding and respond in healthy ways. Yet, despite this incredible discernment tool God has given us, most of us are reluctant to sit with our emotions for very long—unless, of course, the emotion is gladness or joy. Some of us struggle even to name our emotions. Why is this? Barriers to Healthy Emotional Expression Understanding the barriers we face helps us to address them. So, let’s explore three barriers to healthy emotional expression. See if one or more of these resonates with you. 1. Our resistance to pain makes sense neurologically. All pain, whether mental or physical, has a common neurological circuitry. The brain perceives emotional distress as a threat and processes it in a way similar to physical pain. Because we’re hardwired to react to threats with a fight-flight-freeze-fawn response, most of us attempt to eliminate or fix (fight), minimize or run from (flight), numb and ignore (freeze), or please and appease (fawn) painful emotions. 2. Painful emotions are uncomfortable. When we respond to a perceived threat with fight, flight, freeze, or fawn, the sensation generated by our body chemistry is anxiety, which is intended to motivate us to take action to escape the threat or danger in some way. Because anxiety is uncomfortable, we naturally want to avoid it. Digging beneath the anxiety to identify the underlying emotion and then listen for what it wants us to know can feel like work, which tends to accentuate our discomfort. 3. Socialization plays a major role in our tendency to resist painful emotions. Many of us grew up thinking that showing emotion is showing weakness or inferiority. Our culture encourages us to be strong, independent, and resourceful, making the most of the hand we’re dealt. Did you ever hear, “Stop crying or I’ll give you something to cry about,” or “It could be worse; other people have bigger problems than this,” or something similar? As a result, we come to believe that crying in the presence of others is neither advisable nor acceptable. No wonder most of us say “I’m sorry” when we begin to cry in the presence of others! One of the things find myself saying repeatedly in spiritual direction is, “No need to apologize. You never have to feel sorry for showing emotion.” For many of us who are part of a faith community, showing emotion is not necessarily about showing weakness but about revealing a weak faith. Tragically, strong faith often is conflated with emotional control. The erroneous thinking is that those who rely on God are in control of their emotions, while those who are weak in faith are more outwardly emotional. To illustrate this way of thinking, consider a few examples. Have you ever attended a funeral and heard someone say, “She’s holding it together and doing so well; she has such strong faith”? Though it may be true that she has strong faith, a lack of emotional expression is not evidence of that faith but, in fact, might be the result of shock or denial—two stages commonly experienced early in grief. Or, have you ever been struggling emotionally only to have some well-meaning soul offer a spiritual platitude or scripture verse as a spiritual Band-Aid for your pain? Rather than validating your pain and compassionately witnessing your expression of that pain, their discomfort with your outward expression of emotion compels them to try to fix or soothe it. Or, have you ever told yourself something along these lines: “I don’t know why I’m being so emotional about this. I know God is in control. God’s got this.” While it’s true that God is in control, it’s also true that God gave you the gift of emotions to help you navigate the challenges of life. Trusting God does not mean pushing down our emotions. In each of these examples, spirituality is used as a shield or defense mechanism, rather than allowing ourselves and others to feel our emotions and work through them. This is called spiritual bypassing, and it is a subtle yet harmful way of using faith to avoid painful emotions. Here's the reality: Any sentiment, whether spiritual or otherwise, that denies the reality or depth of our pain and the necessity for it to be expressed and witnessed by others only delays the healing process. Do you relate to these three barriers? If so, it simply means you’re human. The good news is that when we stop putting up barriers and trying to resist our emotions, real healing can begin. What We Resist, Persists Another true saying you may have heard is, What we resist, persists. Though we may be successful in suppressing—or consciously blocking—painful emotions for a while, eventually they will seep out sideways or demand our attention in other ways, such as depression, addiction, or even physical illness. Because suppressing emotions keeps the fight-flight-freeze-fawn response activated, the body is continually under attack from stress hormones, causing inflammation and a higher propensity for developing illness or disease. This does not mean that unexpressed emotions are the cause of illness or addiction, but they certainly can be contributing factors. A similar thing happens when we repress emotions, which is an unconscious blocking of unwanted emotions. Sometimes we’re not even aware that we are pushing down painful emotions. We may think we’ve dealt sufficiently with sadness, grief, anger, fear, or shame and have returned to “normal” when we’ve merely pushed down our emotions and moved on much too quickly. The result, as Bessel van der Kolk explores in his book The Body Keeps the Score, is that unprocessed emotions remain within us, affecting our minds and bodies. He encourages and challenges us with these words: “Neuroscience research shows that the only way we can [heal] is by becoming aware of our inner experience and learning to befriend what is going on inside ourselves.” Befriending Our Emotions To befriend is to act as a friend, offering help or support. It is listening to, bearing witness to, and offering loving presence to another. If you’ve ever had someone do this for you, then you know the power of being seen, known, and loved just as you are—whatever you may be feeling. Here’s a liberating truth: We can befriend ourselves by being a loving witness to what is happening within us. We can teach ourselves to become aware of our emotions, allow ourselves to feel them, and offer ourselves self-compassion and understanding. This is a skill that many of us have not been taught, but it is never too late to learn. I've been on a journey of intentionally befriending my emotions for about six years, and I'm still a work in progress. About a year ago God gave me an insight about my childhood that helped me to realize why grieving is so difficult for me. Though I had never understood it this way before, I came to see that loss was a normal part of my childhood. As a preacher's kid in the United Methodist Church, moving was a regular occurrence, which meant picking up and starting over again. Saying goodbye to friends and schools and neighborhoods and church families and routines was a regular occurrence. There wasn't time or space to grieve what was ending or lost. We had to move and adjust quickly to a new environment. No time to grieve or look back. It was full steam ahead. I never learned to sit with my grief, much less welcome it. There is no blame here; it was simply how things were. And I know kids in military families experience this to an greater degree. If I'm honest, I've pushed grief down all my life. I've allowed myself to spend time with grief in very short allotments, but then I'm off again to what's next, what's ahead. Always looking forward, not back. I believed sadness was like one of the friends I had to say goodbye to in order to embrace the new. That was the lie I believed. God has been inviting me—and teaching me—how to sit with grief. I'm a slow learner, but I'm committed to the process. Recently while listening to a podcast on healing from sorrow and grief, I realized that allowing my grief to be witnessed in community has been a missing link for me. So, I have decided to participate in a grief class offered by my church this fall. It feels uncomfortable, and a part of me even thinks it's silly to participate almost four years after my father's passing, but I know I haven't fully grieved his death—and I certainly haven't grieved in community. And I suspect there are many other griefs—some decades old—that have not been witnessed or fully expressed. I'm trying to practice what I teach others, and I know the good will outweigh the hard. Despite the barriers we face when it comes to acknowledging and expressing our emotions, the benefits of doing so always outweigh any momentary discomfort we might feel. Take a look at some of these benefits of befriending your emotions: Sounds good, right? I'm going to keep this list before me, and I encourage you to do so as well. Let's remember that befriending our emotions is a learned skill we can become more proficient in, and it will get easier with practice. Next month I'll be sharing six suggestions, or steps, for befriending and handling our emotions in a healthy way. Until then, every time you are tempted to resist or suppress your emotions, gently remind yourself, "You have to feel it to heal it." I'll be doing the same!

0 Comments

|

Hi, I'm Sally!

I'm passionate about connecting with God and connecting with people, offering spiritual encouragement and companionship. I'm so grateful to be on the journey with you as we walk with God together. subscribeArchives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

Copyright 2019 Sally Sharpe Spiritual Direction |

Proudly powered by Weebly

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed